A big part of winning a war is being able to produce the materials and vehicles needed to continue fighting that war.

Aircrafts, trucks, tanks, and ships are just some of the vehicles necessary to a war effort.

In order to have a constant stream of these arriving at the front lines, you need raw materials – as well as the industrial workforce and infrastructure to build them, of course.

During any war, it’s natural for certain materials to become scarce.

And this was exactly the case in both World War I and II with steel.

As each war dragged on, steel became unseen in civilian use as the military requisitioned it all to create the vital weapons, munitions, and vehicles needed on the front lines.

As such, production of civilian vehicles became somewhat an afterthought in the face of necessary military machines.

The World War I Emergency Fleet

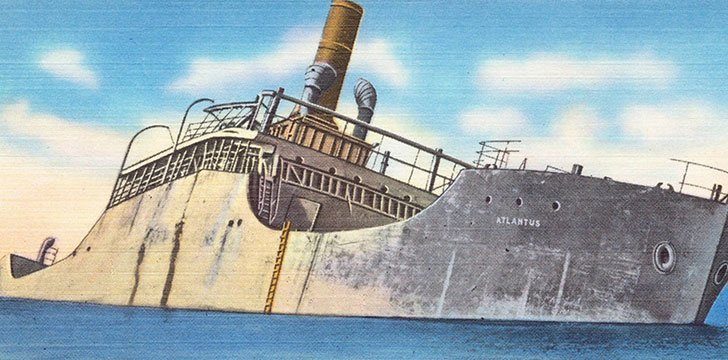

As the First World War seemed to go on without an end in sight, steel started to become scarce, and the U.S. had an idea.

To counter the more important military uses for steel, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson approved the construction of 43 concrete ships.

After all, concrete was a solid material that could take some punishment, plus it was fairly buoyant and thus very suitable ship-making material.

With a budget of $50m for the total fleet of ships, construction began in late 1917.

However, by the time the war had ended only 12 of the total 43 had been built.

The 12 concrete ships were sold into civilian service and lived out relatively uneventful lives.

However, one of them, an oil-tanker called the S.S. Palo Alto, was turned into a dance club and restaurant in Seacliff Beach, California.

Even more interesting was the life of the steamer S.S. Sapona that was used as a floating liquor warehouse during Prohibition.

The McCloskey Ships Of World War II

During the Second World War steel, once again, was a scarce commodity.

In 1942, the U.S. Maritime Commission contracted McCloskey and Company of Philadelphia to build a fleet of 24 new concrete ships.

After 20 years of breakthroughs in concrete technology, the new era of concrete ships was lighter, stronger and faster than their World War I predecessors.

Built at a breakneck pace, the ships were launched in late 1943 – 1944 after being built in Tampa, Florida.

Each of the McCloskey ships was named after pioneers in the development and science of concrete.

Two of the ships were purposefully sunk to act as blockships during the Allied invasion of Normandy as part of Operation Overlord, two are currently used as wharves in Yaquina Bay at Newport in Oregon, and seven are still afloat to this day in a giant breakwater on Canada’s Powell River.