In 2010, the Colombian Army was facing a pretty serious hostage crisis, with several groups of kidnapped soldiers being held hostage by armed guerrilla fighters of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (the FARC).

The FARC sent a bit of grainy footage to Colombian Army Colonel Jose Espejo, a straight-talking gent coming up to his retirement after some 22 years of service.

Some of the Colombian soldiers had been hostages for well over 10 years. Worse yet, it could be seen from the footage many were suffering from flesh-eating diseases passed on through insect bites. Colonel Espejo couldn’t stand the idea of retiring with his men still suffering through captivity.

So he got in touch with the one man who had always provided a solid solution to his problems in the past: Colombian advertising legend Juan Carlos Ortiz.

Ortiz had shot to fame for his anti-drug advertising campaigns in Colombia, winning a Gold Lion at Cannes and earning a commendation from Colombia’s first lady.

Ortiz’s anti-drug adverts had earned him the FARC’s ire in the past, as drug running was a major part of their operation. In fact, Ortiz had moved to New York with his family after persistent death threats from the paramilitary organisation.

So when Colonel Espejo called Ortiz, he was all too happy to help.

It was a known fact that the FARC executed hostages at the first sign of Colombian troops, so Colonel Espejo had to get a message to them to be ready to move somehow. And that somehow was where Ortiz came in to the picture.

Ortiz’s Previous Anti-FARC Campaigns

Ortiz had designed irregular advertising and outreach campaigns targeted at the FARC before. In 2008, the Colombian Army air-dropped 7 million pacifiers into the jungle accompanied with a message aimed at female guerrillas: defect for your children and return to civilization.

During the holiday period, the army illuminated giant Christmas trees all throughout the jungle as a way of reminding the guerrillas what they were missing.

They also wrote messages encouraging peace on soccer balls and floated them down the river to be found by the insurgents.

However, this time the advertising campaign would have to be different, more complex.

Ortiz assembled a crack team of Colombian advertisers. Together with Colonel Espejo and other members of the military, they all brainstormed the best way to get a message to the hostages.

How could they send a message without the captors becoming suspicious?

The big question for everyone in the brainstorming sessions was how? How could they send a message without the captors becoming suspicious and executing those awaiting rescue?

Colonel Espejo knew that FARC guerrillas allowed their hostages to have radios. It helped distract them during long hikes from base to base, and it kept their minds from dwelling on escape.

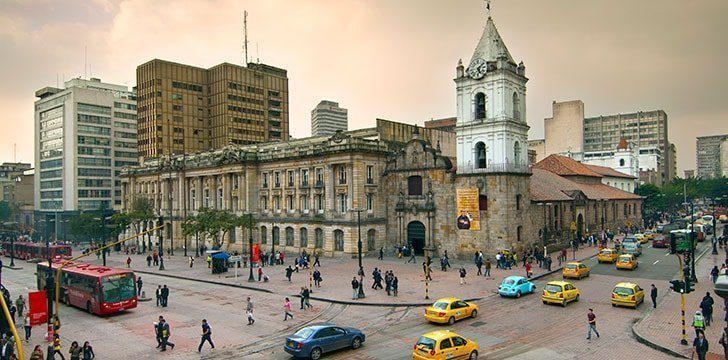

For a long time, radio communications to hostages had been a regularity in Colombia, with the radio show “Voices of Kidnapping.”

It broadcasted on Bogota’s Caracol Radio giving families of kidnapped people a platform to send messages to their loved ones via special call-ins.

Ortiz considered hiding a message in a radio commercial, in the fast-read hardly-intelligible small print at the end of the ad.

Then advertiser Alfonso Diaz came up with a better idea: what about Morse code?

It wouldn’t be the first time Morse code had been used to communicate with hostages, or vice versa, and Ortiz was all for it.

Ortiz described Diaz’s suggestion as “a eureka moment!” saying “We thought about hiding the Morse Code in an advert. Then we thought, how about a song?”

Behind the Scenes of the Secret Song

As a young man, Ortiz had started his career as a musician although it had never gone anywhere. So Ortiz was very keen to write a new hit song.

Ortiz pitched the idea to Colonel Espejo, who liked it because he knew many of the captured soldiers knew Morse code as they were from the Communications Department of the Army.

Furthermore, the FARC fighters were not military trained and wouldn’t detect the Morse code.

In a recording studio, the team started playing around with where to put the Morse code, experimenting with percussion instruments and a keyboard.

They found out that those skilled in Morse code can often read 40 words per minute. However, when sped up the 40 Morse code words just sounded like a dance track and wasn’t understandable.

After a while experimenting, the musical team found that 20 words was the optimum amount of words to go unnoticed but also be clear enough to hear.

With the help of a military policeman skilled in Morse code, they were able to hide a 19-word message in the chorus of the song. It had taken weeks to get the message right and integrate it into the song but now they had it: “19 people rescued, you are next. Don’t lose hope.”

On top of this, the lyrics also drew attention to the Morse code and impending rescue, with some of them saying “In the middle of the night / Thinking about what I love the most / I feel the need to sing / About how much I miss them” as well as adding the lyrics “Listen to this message, brother” just before the message kicks in.

The simple Morse code message simply sounded like a brief synth interlude after the chorus to the unsuspecting ear.

Better Days

The song, titled “Better Days,” was now good to go.

Although Colombian radio stations only tend to play famous pop music like Coldplay or Shakira, all the radio stations in the jungle where the FARC were based were controlled by the Colombian government.

The song was played over 130 small radio stations and heard by 3 million people.

Ironically, the song became a big hit in the jungle areas heavily populated by the FARC, and would be heard multiple times in a day.

A Great Success

In tandem with an ongoing Commando operation, Operation Chameleon, the song helped give countless amounts of hostages the signal to move and escape when soldiers were nearby.

All across the Colombian countryside, “Better Days” was helping people escape years of captivity.

Some hostages were able to escape and even help their fellow hostages escape.

Colonel Ortiz retired from the military as the FARC lost and released swathes of hostages on the back of Operation Chameleon and Better Days, becoming a journalist and still keeping in touch with Ortiz.

Back in 2011 the Colombian Army declassified “The Code” Operation and allowed the song to be entered into that year’s Cannes Lions awards where it won the Golden Lion.

When he had won the award for his anti-cocaine ad in 2000, Ortiz hadn’t enjoyed it too much as it had only bought him and his family death threats and danger.

However, this time, when Better Days swept up that Golden Lion, he was able to take pride in his work.