As those of you who read my articles may know, I’m rather interested in World War II. The whole period of time offers us some of history’s most fascinating stories.

It showcases mankind at its worst, but also at its best.

World War II gave us many interesting stories just as it did many interesting characters.

The focus of today’s article is the story of one Lieutenant Hiroo Onoda of the Imperial Japanese Army Intelligence Corps.

Mission Brief and Deployment

Born in 1922, Hiroo Onoda lived a quiet life until the age of 18, where he joined the Imperial Japanese Army Infantry, going on to train as an intelligence officer in the commando class “futamata” of the Nakano School.

Here he learned guerrilla warfare and intelligence gathering.

On December 26, 1944, Hiroo was sent to Lubang Island in the Philippines with orders to hamper enemy attacks on the island, including destroying the airstrip and the harbor’s pier.

Onoda’s Commanding Officer, Major Yoshimi Taniguchi, had given him orders to live off the land and forbade him to surrender or die by his own hand.

He said “It may take three years, it may take five, but whatever happens, we’ll come back for you. Until then, so long as you have one soldier, you are to continue to lead them.”

Onoda landed on the Lubang Island and linked up with a group of Japanese soldiers previously sent there on a different mission.

The officers in this group of soldiers outranked Onoda, so they denied him permission to carry out his mission.

As a result of the pier and airstrip still being intact, the joint task force of American and Philippine Commonwealth forces was easily able to land on the island and take it in late February 1945.

Within a short time period of the Allied landings, all but Onoda and three other soldiers had died or surrendered.

As the highest-ranking soldier in the small group, Onoda ordered his squad to flee into the hills.

The Mission Begins as the War Ends

After the defeat of the main Japanese forces, Onoda and his three men carried out a guerrilla warfare campaign, engaging with shootouts with local police on several occasions.

In October 1945, Onoda and his squad saw a leaflet announcing that Japan had surrendered.

Later on, after they had killed a cow to eat, they found a leaflet left behind by islanders that said “The war ended on August 15. Come down from the mountains!”

However, Onoda distrusted the leaflet instantly.

Onoda and his crew deduced the leaflet had to be Allied propaganda, a way to trick them into surrendering – something Onoda was under strict orders not to do.

The group also believed their continued shootouts with police were proof the war was still ongoing.

In late 1945, leaflets were airdropped all over Lubang Island with a surrender order printed from General Tomoyuki Yamashita of the Fourteenth Area Army.

The group had been hiding for over a year now, and after examining the leaflet closely they decided it was a fake and chose not to surrender.

Not knowing about the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the group rightly so believed it very unlikely that Japan would surrender.

A Lengthy Campaign of Mistrust

In 1949, one of Onoda’s three men, Private Yuichi Akatsu, left the group and surrendered to Filipino forces six months later in 1950.

This caused the three remaining soldiers to become even more cautious and paranoid.

In 1952, aircraft widened the search parameters, air-dropping letters and family pictures urging the soldiers to surrender, but once again the three soldiers were convinced this was a trick.

In June of 1953, one of Onoda’s men, Corporal Shoichi Shimada was shot in the leg during a shoot-out with local fishermen, whom he assumed were enemy soldiers in disguise, but was later nursed back to health by Onoda.

However, in May 1954, Shimada was shot and killed by a search party after he opened fire on his potential rescuers.

Onoda and his one remaining man, Private First Class Kinshichi Kozuka, carried on their campaign of terrorizing the locals up until 1972.

In 1972 Kozuka was shot and killed as he and Onoda burnt a rice stockpile belonging to a farmer they suspected of being in league with the “enemy” who no longer existed.

An Intrepid Adventurer Ends Onoda’s War

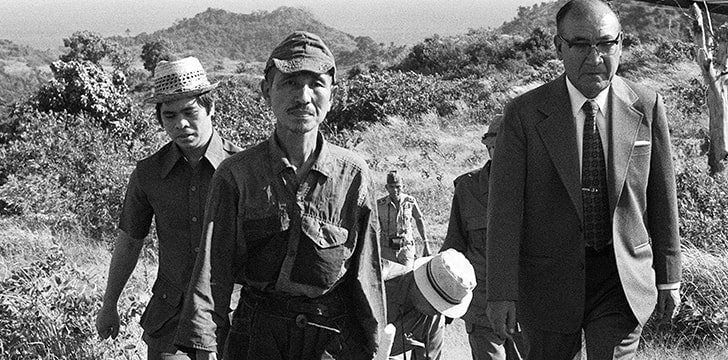

This left just Onoda carrying out his mission until 1974 when a Japanese explorer, Norio Suzuki, found Onoda. Suzuki had been traveling the world, searching for “Lieutenant Onoda, a wild panda, and the Abominable Snowman, in that order.”

After locating the fabled Japanese soldier, clad in the tattered rags of his Imperial Japanese Army uniform, the two became friends.

However, Onoda still refused to surrender.

So Suzuki, having heard Onoda’s story from the man himself, located his former Commanding Officer, Major Yoshimi Taniguchi.

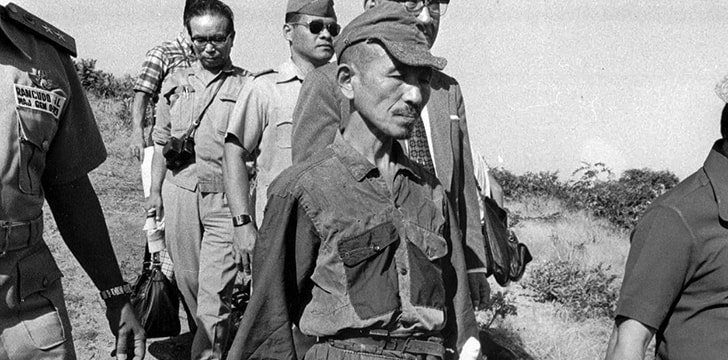

Fulfilling his promise from decades ago, the former Major ended Onoda’s orders in person.

Onoda saluted the Japanese flag, then handed the Major his katana, his still-functioning Arisaka Type 99 rifle, several rounds of ammo, some hand grenades and his family dagger.

Despite being responsible for the deaths of over 30 innocent people during his campaign, Onoda was granted an official pardon by the Filipino government as he believed the war was still going on.

Going Home to A Different Country

Upon returning back to Japan, Onoda was an overnight celebrity.

However, he found it very hard to adjust to life in a country vastly different from the one he had left all those years ago.

He wrote and published an autobiography in 1975, before leaving Japan for Brazil where he became a cattle farmer and later opened up a series of survival training schools in Japan.

In an interview near the end of his life, Hiroo Onoda said:

“Every Japanese soldier was prepared for death. But as an Intelligence Officer, I was ordered to conduct guerrilla warfare and not to die. I became an officer, and I received an order. If I could not carry it out, I would feel shame. I am very competitive.”

Hiroo Onoda passed away peacefully in 2010, aged 91.